"Sorry Nanya, they couldn't revive him. We lost him, beta."

At 6.51 am, Tuesday February 23, 2021, my mother broke the news that my grandfather (my father’s father) had died to me over a Whatsapp message. In a different city, my father would arrive home to my sister to tell her in person. They were going to light a lamp and sit with it. I made my way to the roof to watch the sun just come up over the horizon – the slow lighting of a candle I was somehow just in time for. By the time the dog and I got back down, my sister had me on the phone – our voices breaking a little, our grief shared and multiplied, echoes of feelings inside us, bouncing off echoes of feelings of those in the close family outside us.

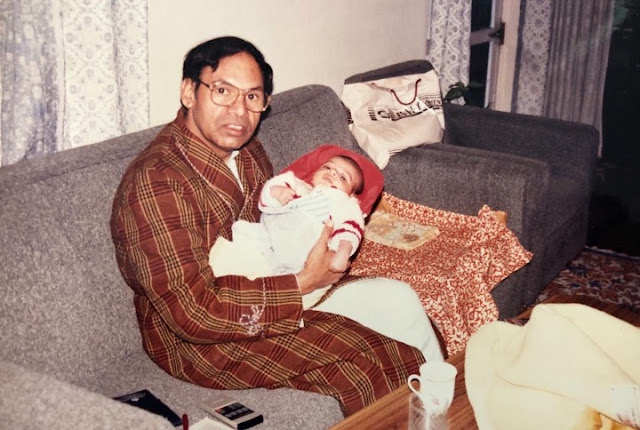

The first person to hold me in the world had just died. Died.

Nearly exactly a year ago, just before the pandemic manifested itself as a permanent fixture in our lives, I had traveled to India prematurely to see my other grandfather who had been hospitalised earlier in the year. Between one flight landing late and another leaving right after, I didn't get to see him, but I spent a third of a day in Delhi visiting with my other two grandparents (my father's mother and his father – Papa, as he was known to his children but also his grandchildren). We had the lunch they have had an iteration of for the last many years of their lives, I attempted our usual tradition of touching his feet and him refusing this quaint ritual, and we shared a cup of tea in the warmth of the last cold Delhi spring day before we knew the extent of the wave that was about to hit us. That would be the last time I would see him.

We had been losing him slowly in the last few years – first his sense of purpose as a working bureaucrat when he retired after a full career working to improve the jagged country we live in, then his hearing, and with that, a little bit, his motivation for social connection. Soon enough, my grandmother was the only one who could get through to him. "Dhiru!", she would call him by her lovename for him, somehow getting his attention even though she was just loud enough for the rest of us to hear, "They're asking how you're doing". His last few years were spent in a haze of love and memories, on the surface 'hi's and 'hello's, but in higher spirits, crystal clear accounts of days from the past that had changed his life, and in so many ways, ours: his wedding, the surprise of being enlisted in it and the procession that followed, finally meeting his wife a year later; his days on the tourism board strategising how to bring out the best in a town, a hotel, a beer factory; how he built his first house brick by brick; how he met each of his grandchildren. Each one a special story he would unwrap like candy at dinners with the family.

Even though he couldn't hear us as well for so many years, even though he seemed lost in a land of memories, he was always crisp in expressing himself – his love and the path of his life full and present. Here was the boy who had gone to school with no shoes and one slate, whose father, a poor farmer, gave up his own food and who knows what else so that his son could study towards a better life than the one he had been born into. He worked so hard and did so well, he flew through scholarships, landing in prestigious Allahabad University and then, wonder of wonders, the Indian Civil Service, rising before dawn each day to ensure that every day, someone was being given a fairer life, a just decision, a glimpse of humanity. So polished, so gentle, so hardworking, they gave him the name with which he would be called his entire life, "Sudhir", with gentleness. Our family's last name.

He set up India's largest (and, I think, first) crafts fair, one that invites various artists and artisans from all over the country each year to a beautiful lake near Delhi to showcase the glorious diversity of the country and continue to nurture traditions that would otherwise die out. He brought home lush silks from foreign travels that my grandmother still shows off. He approved and inspected restaurants in prestigious hotels all over the country – as children, a recurring theme was going for dinner to iconic restaurants in Delhi that my father was invited to as a perk of his work, only to find out that my grandfather had approved them when they were set up years ago. And that I myself returned to on balmy summer afternoons for a coffee and a pastry as a college student in the same city. We are all walking in shadows of footsteps he made.

He suffered little as he went, by some standards (though what are ‘standards’ when talking about pain?). My father and mother were both positive on the phone about that. That even with eight months of discomfort, of not being able to breathe well, sleep restfully, of blood clots and heart attacks, he wasn't in much pain. Even as he passed, he had the best medical care, he had people around him that he loved, his family at home and on video calls connecting with him when they couldn’t be. And he was there, he was fully there, asking and responding and recounting and blessing us, nearly more clearly than he had been in years. We are so grateful for that. (A couple days ago, he had fallen asleep with his eyes open. When my mother went to check on him, heart literally skipping a beat in case the inevitable had happened, he raised an arm he hadn't been able to lift in months stick straight and said, "I'm right here!" He was, and he is.)

My grandparents’ one wish for all their grandchildren was that we study hard and get steady jobs at good organisations. My decision to work on poverty alleviation and representing marginalised groups came from this understanding of my family's complicated journey into being where they were, and that not everyone was so lucky, so hardworking, so unconditionally loved in a tough, tough world. Being a Sudhir is an everyday reminder that what we have is so precious, so rare, earned through sweat and sleepless nights, achieved with the pure fact of selfless love, family support, non-judgement. Our family is a place where we discuss everything exceedingly democratically – even the youngest member has a valid say in issues from what we are going to snack on that evening down to the colour of the car we are going to buy. In the middle of the casteist, patriarchal, religious fanatic country I come from, I grew up in one of the only bubbles of absolute freedom and equality. What a remarkable privilege.

In our last conversations, my grandfather asked me repeatedly if I had already moved to Geneva to work with the international organisation I work for, perhaps losing track of the muting of major life decisions during the pandemic. It seemed to satiate him that the answer was: yes, even if remotely, I was working in a serious job doing good things for the world, spending my life in service to extend that privileges we had (the privileges he had forged for us) to others without our platform in the world. And could anything else be a more beautiful note of confidence to carry him with us forever than that?